Frailty & COVID-19: why, what, how, where & when?

Please note: **The CFS has not been widely validated in younger populations (below 65 years of age), or in those with learning disability. It may not perform as well in people with stable long term disability such as cerebral palsy, whose outcomes might be very different compared to older people with progressive disability. We would advise that the scale is not used in these groups. However, the guidance on holistic assessment to determine the likely risks and benefits of critical care support, and seeking critical care advice where there is uncertainty, is still relevant.**

Why?

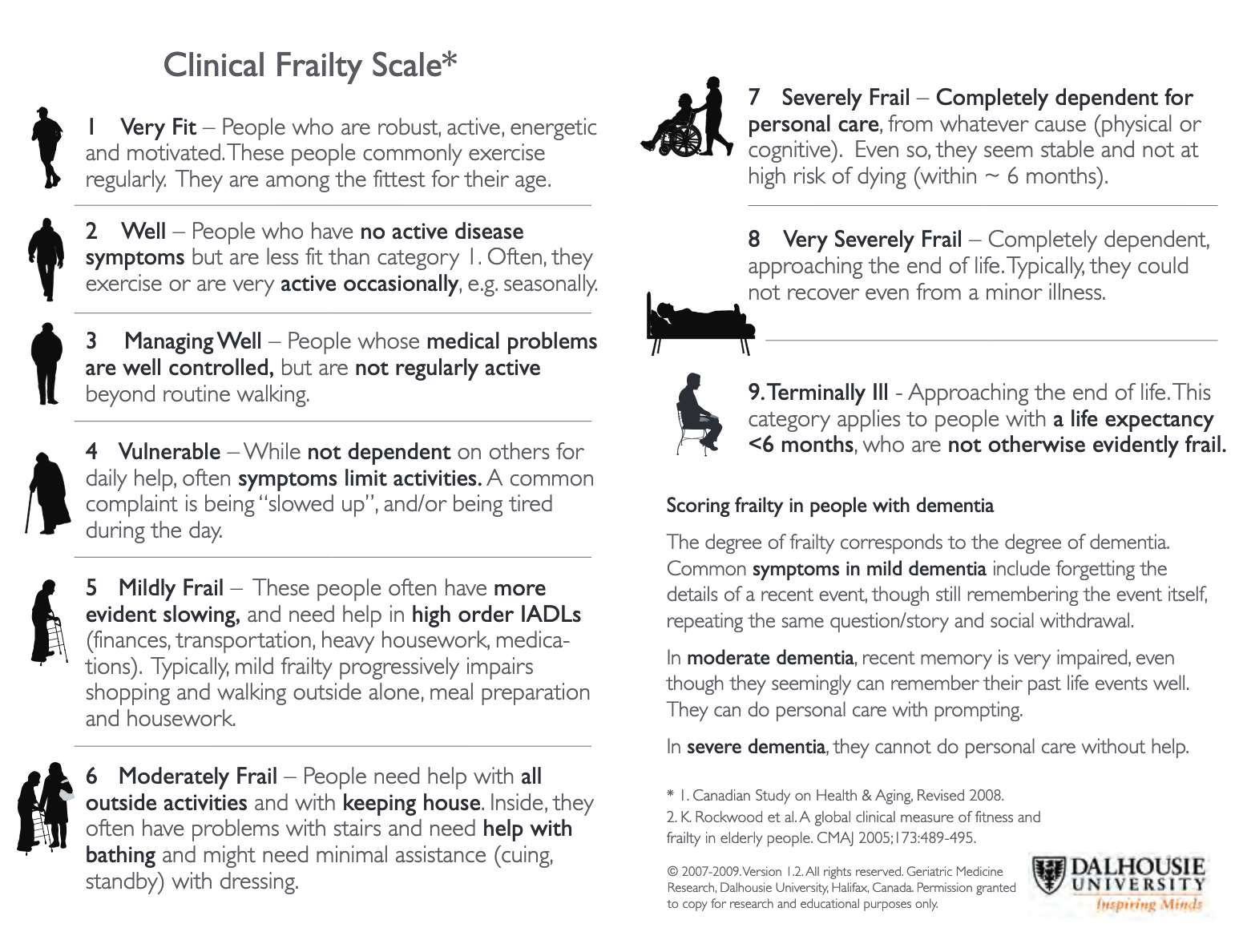

Rapid NICE guidance produced in response to the COVID outbreak clearly outlines the importance of identifying and grading frailty using the Clinical Frailty Scale. The purpose is to identify patients who are at increased risk of poor outcomes and who may not benefit from critical care interventions.

What?

Frailty is a state of increased vulnerability to poor resolution of homoeostasis after a stressor event, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes(1). It can be assessed quickly and simply using the Clinical Frailty Scale (Appendix 1). Frailty identification should take no more the one minute(2); the more you use the scale, the quicker it will become.

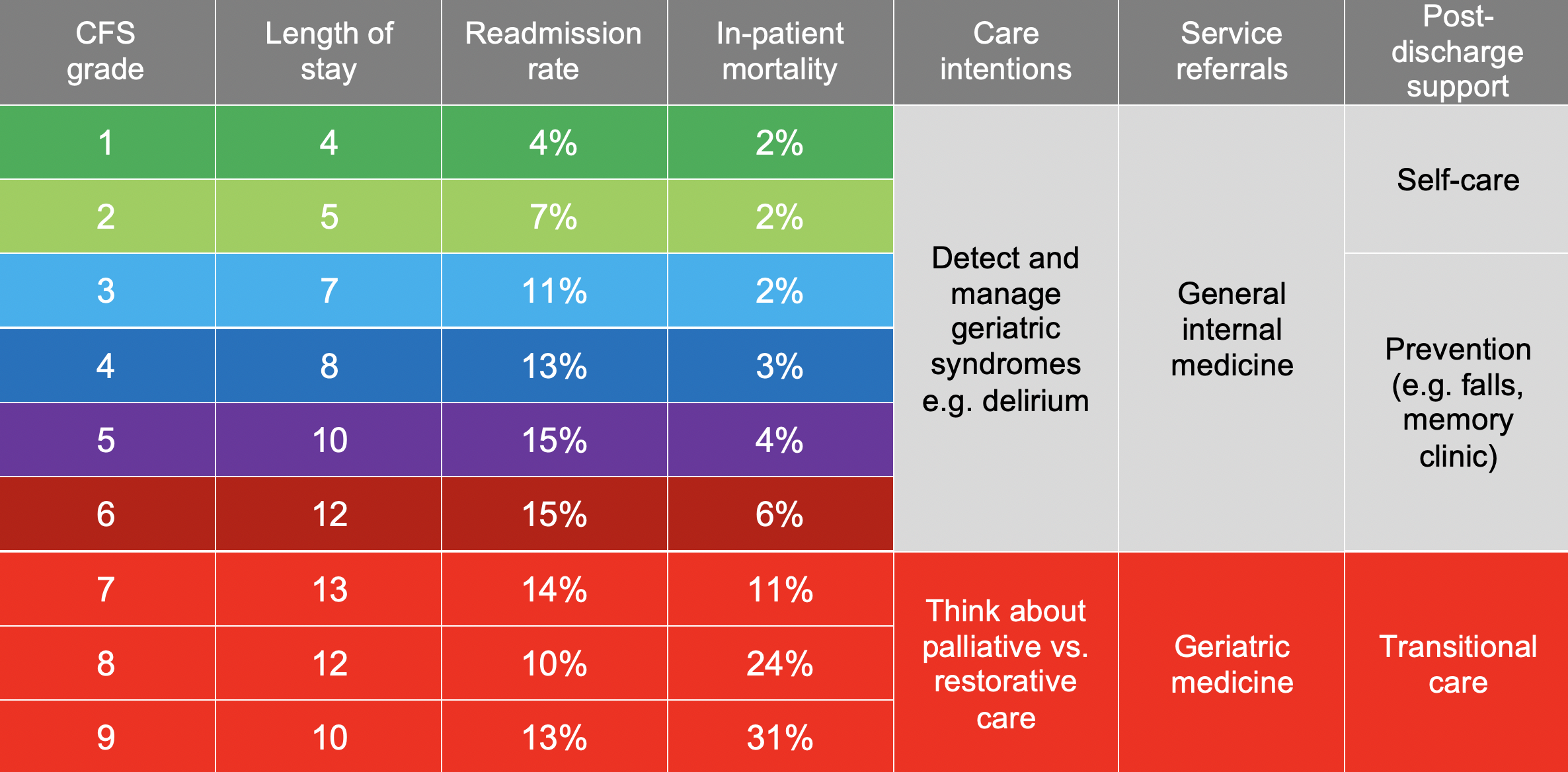

The CFS is a reliable predictor of outcomes in the urgent care context (Appendix 2)(3-9); critical care specific outcomes are summarised in Appendix 3. Like any decision support tool, is not perfect and should not be used in isolation to direct clinical decision making. It will sensitise you to the likely outcomes in groups of patients, but clinical decision making with individual patients should be undertaken through a more holistic assessment, using the principles of shared decision making.

How?

The CFS can be undertaken by any appropriately trained healthcare professional (doctor, nurse, health care assistant, therapist etc.) with training and support.

Ask the patient or their carer/next of kin/paramedics/care home staff what their capability was TWO weeks ago.

DO NOT base your assessment on how the patient appears before you today.

Decision makers using the CFS to inform clinical management MUST check the score to ensure that it is accurate.

DO be careful about differentiating between CFS 6 and 7:

CFS 6 (need help with outdoor activities and some help with basic activities) – all cause mortality during admission to acute hospital = 6%

CFS 7 (completely dependent for personal care) – all cause mortality during admission to acute hospital = 11%

When?

The CFS should be assessed at ED triage, or any first point of contact with acute care (including by paramedics), alongside Early Warning Scores. It should be reassessed after two weeks if clinically relevant.

Using CFS in practice

DO remember that the CFS has only been validated in older people; it has not been widely validated in younger populations (below 65 year of age), or in those with learning disability. It may not perform as well in people with stable long term disability such as cerebral palsy, whose outcomes might be very different compared to older people with progressive disability. We would advise that the CFS is not used in these groups.

However, the guidance on holistic assessment to determine the likely risks and benefits of critical care support, and seeking critical care advice where there is uncertainty, is still relevant.

Ask the patient, their carer/next of kin/paramedics/care home staff what the patient’s capability was TWO weeks ago. The assessment should NOT be based on how the patient appears before you today. Decision makers using the CFS to inform clinical management MUST check the score to ensure that it is accurate.

TOP TIPS TO HELP YOU USE THE CFS

Professor Ken Rockwood and colleagues have written a paper on COVID-19, frailty and long-term care, and the potential implications for policy and practice, which can be found here.

Alice Warren, Staff Nurse

ED, Leicester Royal Infirmary

Anuja Chalishazar, Junior Doctor

ED, Leicester Royal Infirmary

Jay Banerjee, Consultant in Emergency Medicine

ED, Leicester Royal Infirmary

Professor Ken Rockwood

Professor of Medicine, Dalhousie University

Appendix 1: clinical frailty scale

The Clinical Frailty Scale was developed at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada. The license is free for research, educational, and not-for-profit health care. Users are asked to sign a form agreeing not to change or commercialize it. request / correspondence can be sent to the Geriatric Medicine Research Unit gmru@dal.ca

Appendix 2: Outcomes in acute care (NOT COVID specific) associated with frailty

Below are (unpublished) data displaying the time to death from ED attendance for different frailty scores, over two years.

Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier survival plot for time from ED arrival to death, by CFS category, nr = not recorded:

Appendix 3: Critical care outcomes associated with frailty

Frailty measured using the CFS or Frailty Index is associated with higher in-hospital (relative risk (RR) 1.7) and long-term mortality (RR 1.5)(10). Frail patients were less likely to be discharged home than fit patients (RR 0.6)(11). Additional studies undertaken since these reviews support the importance of frailty as a prognostic marker (Table 1).

Table 1 Outcomes from ICU using frailty as a predictor

References

1. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England) 2013;381:752-62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

2. Elliott A, Phelps K, Regen E, et al. Identifying frailty in the Emergency Department-feasibility study. AGE AND AGEING 2017;46(5):840-45. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx089

3. Cardona M, Lewis ET, Kristensen MR, et al. Predictive validity of the CriSTAL tool for short-term mortality in older people presenting at Emergency Departments: a prospective study. Eur Geriatr Med 2018;9(6):891-901. doi: 10.1007/s41999-018-0123-6 [published Online First: 2018/12/24]

4. Romero-Ortuno R, Wallis S, Biram R, et al. Clinical frailty adds to acute illness severity in predicting mortality in hospitalized older adults: An observational study. Eur J Intern Med 2016;35:24-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.08.033 [published Online First: 2016/09/07]

5. Wallis SJ, Wall J, Biram RW, et al. Association of the clinical frailty scale with hospital outcomes. QJM 2015;108(12):943-9. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv066 [published Online First: 2015/03/18]

6. Basic D, Shanley C. Frailty in an older inpatient population: using the clinical frailty scale to predict patient outcomes. Journal of Aging and Health 2015;27:670-85. doi: 10.1177/0898264314558202

7. Provencher V, Sirois M-J, Ouellet M-C, et al. Decline in Activities of Daily Living After a Visit to a Canadian Emergency Department for Minor Injuries in Independent Older Adults: Are Frail Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment at Greater Risk? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2015;63(5):860-68. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13389

8. Hubbard RE, Peel NM, Samanta M, et al. Derivation of a frailty index from the interRAI acute care instrument. BMC Geriatr 2015;15(27):015-0026.

9. Kahlon S, Pederson J, Majumdar SR, et al. Association between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge from hospital. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne 2015;187:799-804. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150100

10. Darvall JN, Gregorevic KJ, Story DA, et al. Frailty indexes in perioperative and critical care: A systematic review. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics 2018;79:88-96.

11. Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A, et al. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Medicine 2017;43(8):1105-22.

12. Darvall JN, Bellomo R, Paul E, et al. Frailty in very old critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand: a population-based cohort study. Medical Journal of Australia 2019;211(7):318-23.

13. Guidet B, de Lange DW, Boumendil A, et al. The contribution of frailty, cognition, activity of daily life and comorbidities on outcome in acutely admitted patients over 80 years in European ICUs: the VIP2 study. Intensive Care Medicine 2020;46(1):57-69.

14. Langlais E, Nesseler N, Le Pabic E, et al. Does the clinical frailty score improve the accuracy of the SOFA score in predicting hospital mortality in elderly critically ill patients? A prospective observational study. Journal of Critical Care 2018;46:67-72.

15. Zeng A, Song X, Dong J, et al. Mortality in Relation to Frailty in Patients Admitted to a Specialized Geriatric Intensive Care Unit. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences 2015;70(12):1586-94.

16. Shears M, Takaoka A, Rochwerg B, et al. Assessing frailty in the intensive care unit: A reliability and validity study. Journal of Critical Care 2018;45:197-203.

17. Silva-Obregon JA, Quintana-Diaz M, Saboya-Sanchez S, et al. Frailty as a predictor of short- and long-term mortality in critically ill older medical patients. Journal of Critical Care 2020;55:79-85.